Together, We Succeed.

Citizen Science is Only One Step in Ornithological Research

Ornithology is a science. What makes this so is that there are observations made about bird populations or bird behaviors, and these lead to hypotheses about what causes the observed patterns. Then scientists develop a method for collecting and analyzing data to determine whether the hypothesis is true. Lastly, a frequently forgotten step in the scientific method is presenting the study to peers and the general public. In this blog post I will talk about two specific steps in this process: the collection of data, and the presentation of it in published form.

The collecting of data does not need to be done by people with graduate degrees. Ornithology really benefits from participation by laypersons and hobbyists and even children in the collection of data; this is called “citizen science.” Examples of citizen science in ornithology is the upcoming Christmas Bird Count by the National Audubon Society and Project FeederWatch by the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.

I grew up with a bird feeder in my backyard, and I signed up to record bird observations for Project FeederWatch in the first year that the program was available in the United States. At the age of 13, I was one of 4,000 participants in the winter of 1987-1988. Today, there are more than 20,000 participants (1). Obviously, one of the great things about citizen science is that it engages young people who may eventually make a career out of it (like me!). Or, it may help people—young and old—to better appreciate the environment and work toward its conservation and protection.

There is a third benefit to citizen science, and that’s the “science” part. As I explained earlier, the data that people are collecting can be used to answer scientific questions. This part that requires some extra schooling and experience. According to the Project FeederWatch website, there have been 38 scientific publications written using the citizen-collected data (about 1.2 articles per year). I’m surprised this number isn’t two times as large, but I know Cornell isn’t slacking. It takes time to build a dataset that covers the continent evenly enough to look for geographic and seasonal fluctuations in bird populations.

Each of those 38 articles took a lot of effort to publish. Authors must use succinct and technical language, have great patience, and know how to navigate the editing process. Scientific articles must go through peer-review, and there is no guarantee they will end up published. The steps involved are as follows. First, authors submit their draft to a journal editor. The editor then sends the draft to three reviewers who are scientists familiar with the topic (2). The reviewers read the draft and make comments on the validity of the methods used to collect the data and whether the analysis of the data by the author convincingly supports their conclusions. The reviewers’ comments are shared with the author, but not their names (3).

Upon receipt of the three reviews, the editor must decide whether the article is worthy of publication. Often, the author is required to make revisions in response to the reviews. This is difficult work, since sometimes the reviews by the three peers do not all agree. Science is a messy process. I guess we all know that better now, since the pandemic began. Public health guidelines have changed over and over to reflect the constant—and purposely conservative–revision process that science has always had. It’s just far more public than before.

Getting back to the publishing of ornithology research, I want to talk about being a peer reviewer. I’ve been recruited to review five articles this year for two journals, one called ‘Birds’ and another called ‘Biology’ (4). These particular journals are controversial because unlike most, they are published by for-profit enterprises. Their business model depends on publishing lots and lots of articles online in order to build up their reputation and readership. If more scientists get used to reading articles from these journals, then more scientists will send their manuscript drafts to these journals. There are large submission fees associated with journal submission to these journals, and that’s how they make most of their profits (5). This is all different from a more traditional journal that is run by a non-profit organization, in which there is no financial incentive to publish papers that don’t meet some high threshold of quality.

With that said, I have less concern about Birds and Biology (beyond their uninspiring titles) now that I’ve been a reviewer for them. This is because both the journal editors and reviewers respect the process. For example, when reviewing a draft article, the reviewer must make a recommendation. The choices are:

- Accept the work in present form,

- Accept the work after minor revision (corrections to minor methodological errors and text editing),

- Reconsider after major revision (control missing in some experiments), or

- Reject the paper (the article has serious flaws, additional experiments needed, research not conducted correctly).

For the article I just reviewed this week for Birds, I selected the “accept after minor revision” box. Having first submitted my review, I can now see what another anonymous reviewer has said about the same article—“reject.” The editor is waiting on the response of a third reviewer, but clearly there is a big problem here. I liked the article, and someone else did not. It would be hard to reconcile those views, so the editor is probably going to reject the paper. I say this because that is what happened in August with a different article when I selected the “reject” box and two other reviewers both selected the “accept after minor revision.” In that case, my opinion was the outlier and still led to the article being rejected.

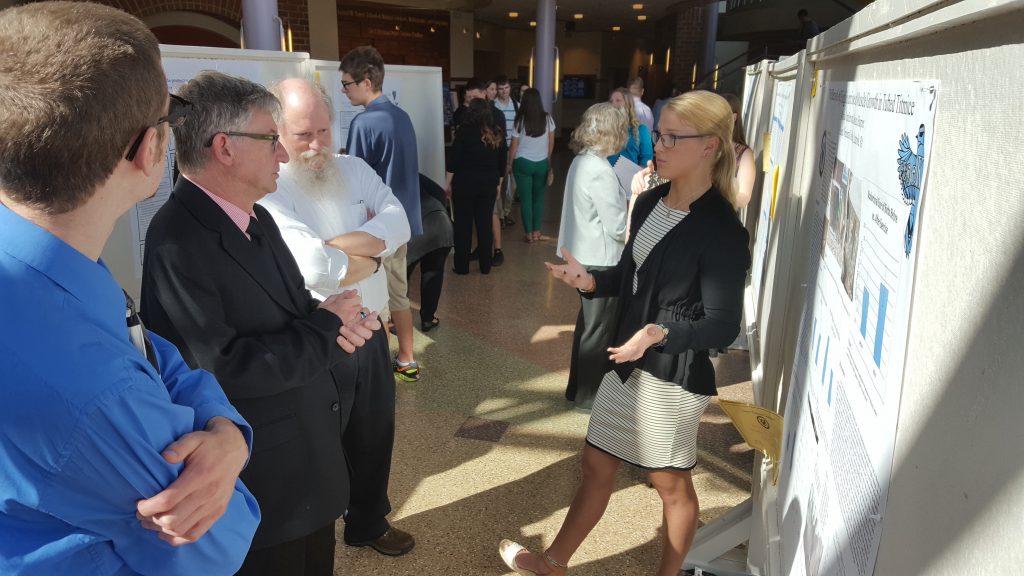

I started this blog post talking about citizen science but then veered into the tedium of how scientific papers are published. These two topics are linked in that they are both steps in the scientific method, and yet they contrast a lot. Citizen science in ornithology allows researchers to obtain vast amounts of data, and that is truly great for the ultimate purposes of our field—to understand how and why birds do what they do, to study how birds relate to other living creatures in their ecosystem, and to protect them from human harm. At the same time though, the collection of data is not enough to achieve those purposes. We need trained scientists to develop the methods of data collection used by the citizen scientists, and we need trained scientists to analyze the data so that it can be used in compelling ways to answer important questions. For these reasons, we need more trained scientists, and I’m happy to say that Biology and Environmental Science students at Saint Vincent College get the training they need to do this scientific work. I look forward to the time when I get to be a peer reviewer for one of my former students. I can’t promise to “accept their work in present form,” but I am confident that I’d never need to check the box that says “reject.”

Endnotes

- This information is from https://feederwatch.org/about/project-overview/

- There are numerous scientific journals and each one has different rules, formats, and policies for peer review. I’m generalizing the steps here, since some editors will send the draft to only two peer reviewers and some may send the draft to four. Also, the familiarity of the reviewer with the topic will vary. Sometimes an article is on something so unique that it is hard to find peer reviewers familiar with the topic. That is not the case with bird population studies using FeederWatch data, though.

- Many scientific articles have multiple authors, but one is usually designated to be in charge of responding to peer review and revising the draft, so I’ve chosen to say “author” instead of “authors.”

- A journal is a compilation of published articles on different topics, issued all at the same time, like a magazine with separate articles. Once published in a journal, the author no longer owns the article and no royalties are paid. Thus, scientists do not make money on publishing articles; in fact, it costs money to do so.

- This information is from https://formadoct.doctorat-bretagneloire.fr/c.php?g=654641&p=4598876

This article is written by Dr. Jim Kellam, Associate Professor of Biology at Saint Vincent College.